A Beginner's Guide to Layli Long Soldier and Indigenous Activism

To begin, one could familiarize themselves with the Oglála, one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people and from where Long Soldier hails. Together with the Eastern Dakota (Santee) and Western Dakota (Wičhíyena) subcultures, the Lakota and Dakota make up the Seven Council Fires; the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ. Today, they reside on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation of Southern Dakota, which through struggle, exile, trade, starvation, war, and legislation with the colonial United States throughout the 18th century and into the modern day, the Sioux were permitted to reside on and maintain.

To follow, one could take to learning the colonial history of the United States, and of the various compounding genocides of Indigenous tribes that occurred to reach the modern settlement of North America, the “New World”. Though the history varies vastly between the tribes, regions, lands, and colonial powers, one could begin by taking to the overarching themes and present applications: the eradication of not just peoples, but monuments, culture, history, art, dance, song, health, spirituality, quality of life, government, structure, and peace. Whether it be the deposition and overthrow of the last queen of Hawai’i, Liliʻuokalani, the illegal occupation of the Sioux-owned Black Hills (Pahá Sápa) and unjust construction of Mount Rushmore upon the sacred Six Grandfathers (Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe) mountain, or federal United States health agencies sending Seattle-based Indigenous populations body bags following a request for coronavirus medical aid in 2020[1], one should become well-acquainted with the ineffable colonial violence modern America is built on.

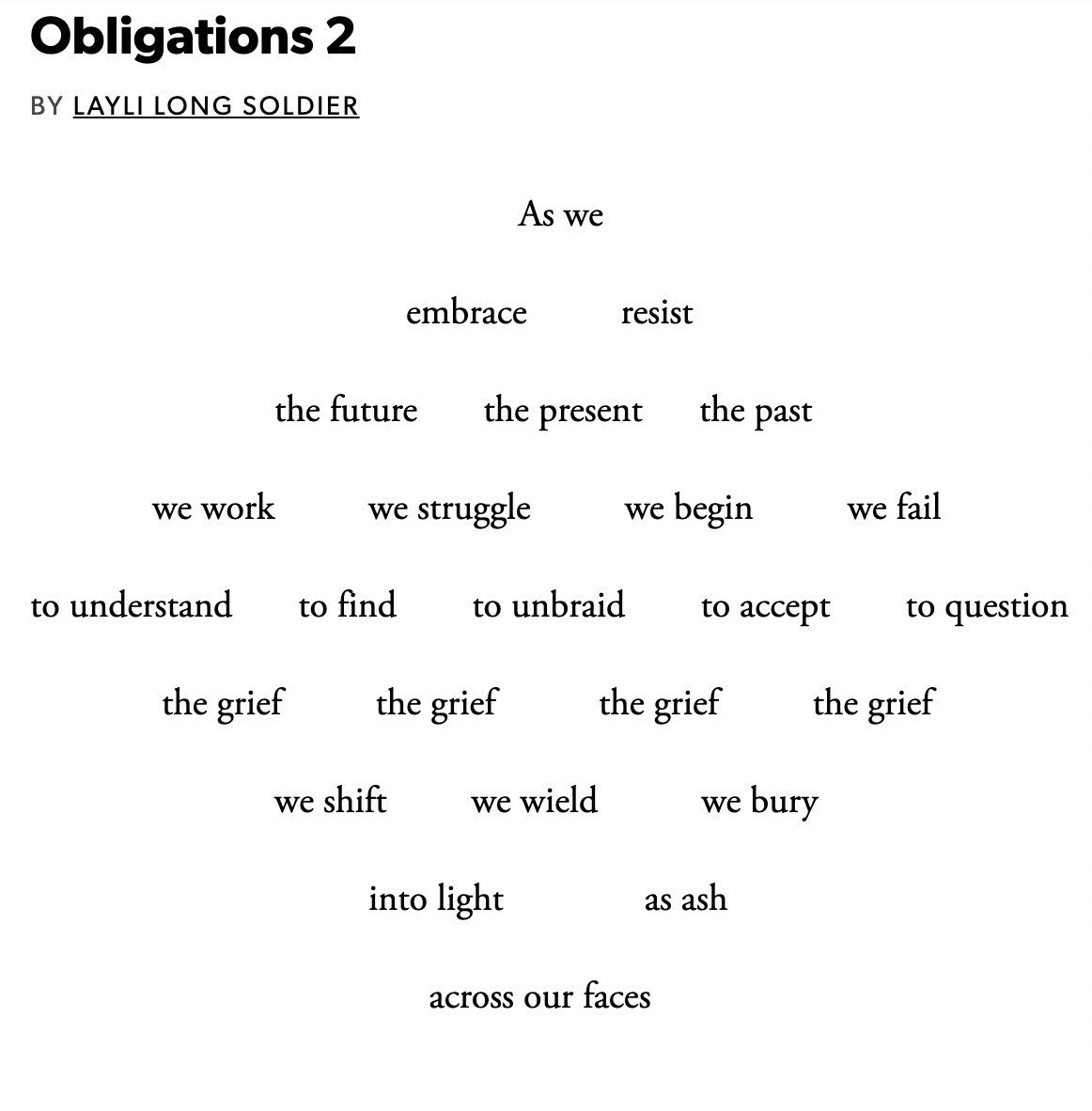

Next, one could finally begin to read a Layli Long Soldier poem. Perhaps one could begin with a poem from her very own publication, Whereas, like “Ȟe Sápa, Four”, or with one of her independently published poems, such as “Irony”. Or perhaps, one could begin with the poem I was introduced to Layli Long Soldier through: “Obligations 2”.

Finally, one can get to know Layli Long Soldier.

Layli Long Soldier is an Oglala Lakota author, poet, artist, feminist, and activist, who has been publishing her written work since 2010. Receiving her BFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts and an MFA from Bard College, Long Soldier’s primary publications include the chapbook Chromosomory in 2010 and the full-length Whereas in 2017. Long Soldier has become quickly acclaimed throughout her career, earning nominations for the 2017 National Book Award for Poetry and the 2018 Griffin Poetry Prize, and winning the 2015 Lannan Literary Award, the 2016 National Artist Fellowship Award from the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, the 2016 Whiting Award, the 2017 National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry, and the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award. Since, Long Soldier has worked as a poetry editor at Kore Press[2] and as an English professor at the Navajo-owned Diné College.

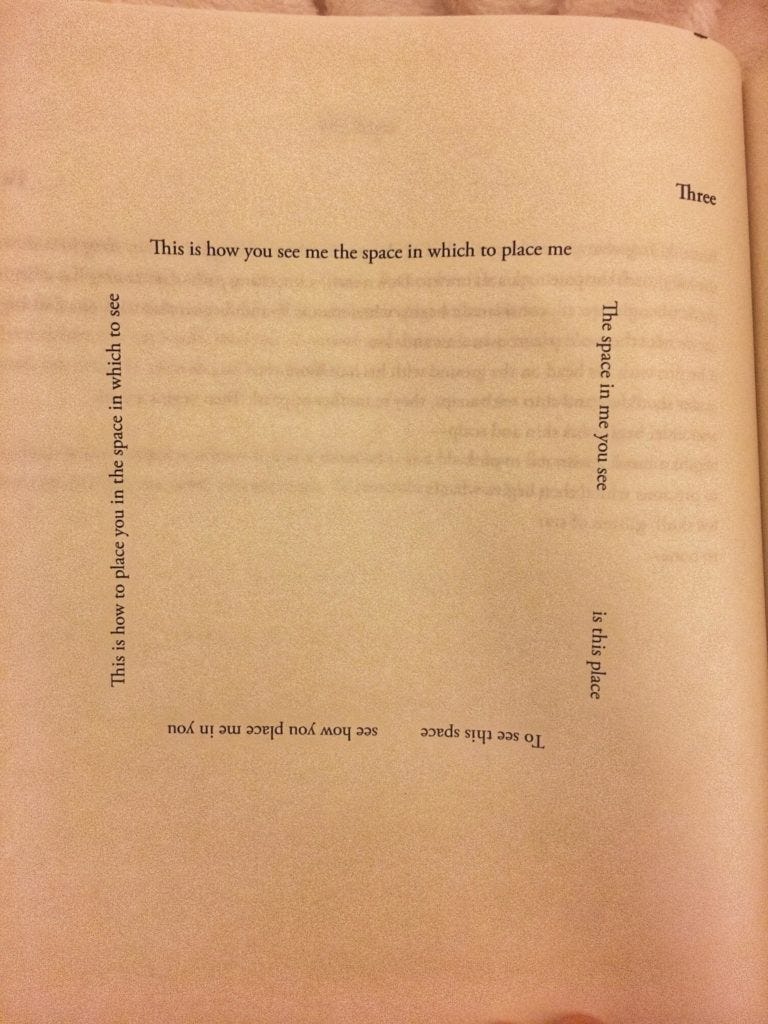

Being Native Lakota, much of Long Soldier’s art advocates against the continued systemic oppression of Indigenous populations in America[3]. Long Soldier’s Indigenous identity, in fact, is integral to and inseparable from her poetry and writing. Not only does she incorporate much of the Lakota language into her writing, but so too does she integrate Native lore, mythology, and history into her prose. Additionally, Long Soldier will occasionally utilize blank space and unique text placement in her poems—such as in “38” and “Obligations 2”—as a means of conveying the unsaid.

Ultimately, while Layli Long Soldier’s activist art and writing has become well-acclaimed in the general American hemisphere, a lot of her writing, especially when it pertains to her experience being Oglala Lakota, is destined to pertain mostly to other Indigenous audiences. Her book, Whereas, for example, is an extensive collection of poems mostly involving the Indigenous experience, especially as it pertains to her own daughter—what it means to be Lakota, what it means to pass that down to someone, what it entails (if anything?).

While the Land Back movement—with its origins in the 2010s and rise in popularity in the 2020s—has become decently well known among certain sects of the American public, it unfortunately and ultimately lacks the awareness that many of its fellow modern activist campaigns have. While the Indigenous people of America are slowly gaining more ground in the fight for equality, Indigenous rights are a formidable bastion to many Americans. To many, acknowledging Indigenous peoples, let alone their sovereignty, is a slippery slope to having to acknowledge that the government you live under, the land you reside on, the people you live beside, and the integrity of your nation might not be as sound as you’ve always believed them to be. Many people refuse to educate themselves on what land return to the Indigenous tribes of America would actually look like, and tend to fearmonger on their rightfully bought and maintained property being “taken away” or “suddenly not being theirs anymore”—an ironic statement when you think about the origin of it all.

To get to know activists like Layli Long Soldier can therefore potentially prove intimidating to those who aren’t well-acquainted with the Indigenous people of America and their history. After all, you could probably out-write the Bible itself if you were to put every crime committed against Indigenous people to paper. To many, acknowledging Indigenous people and their activism comes at the risk of loosening the foundation of their very own worldview. When you first read Long Soldier’s works, without some supplementary knowledge you may be left wondering, “What on Earth does this say?” or “What does this mean?” But ultimately, all it takes to get to understanding is a few small steps, a little bit of research, and a sense of hope—that of which is found in overwhelming dosages in Long Soldier’s works herself.

After all, the first poem of Layli Long Soldier’s that I read, “Obligations 2”, was only tangentially related to the Indigenous experience at first glance itself. Without knowing Long Soldier herself, the themes and artistic direction would still come through strongly—which is what stunned me personally—but you might not be able to implicitly connect it to the Native experience without that contextual knowledge. Nonetheless, coming from someone who’s only had minimal interactions with my Indigenous peers myself (limited mostly to the farmers markets of Tucson, Arizona and the internet), it truly only takes an open mind, a Google tab, and a little bravery to bridge that distance.

[1] Erik Oritz, “Native American Health Center Asked for COVID-19 Supplies. It Got Body Bags Instead.” (NBC News, May 5 2020.)

[2] “Layli Long Soldier.” (Poetry Foundation.)

[3] Annamae Sax, “Layli Long Soldier: Respecting the Sentence.” (Claremont Graduate University, December 18 2018.)